Many 3D games require some sort of collision detection between 3D objects. Sometimes it’s possible to do this with some basic math and bounding boxes and bounding spheres. But when shapes get more complicated, the math and code gets complicated as well. Luckily LibGDX comes with a wrapper around Bullet. Bullet is an open source 3D collision detection and phyisics library, making it possible to add collision detection with just a few lines of code. This tutorial will guide you in using the LibGDX 3D physics Bullet wrapper.

Being written in C++, the Bullet library performs really well. It is used by many commercial games and movies. But that also introduces a problem for us. With LibGDX you write your code in Java and you can’t directly use a C++ library from within Java. In fact, the design of the two languages is so different that in many cases a one on one translation without performance loss isn’t possible. This is where the “wrapper” comes in. The wrapper is a layer (or “bridge”, if you prefer) between the Bullet library and your Java application, while maintaining performance. Because of this, the wrapper adds some changes to the Bullet API.

As you might imagine, working with the wrapper is therefor a bit different than working with a regular Java library. In this tutorial I assume that you’re new to both the wrapper and the Bullet library. If you already have experience with using the Bullet library, this tutorial still might be useful. But you probably also want to have a look at this wiki page, where the important changes that the wrapper introduces are outlined.

For this tutorial I assume that you are already familiar with LibGDX and its 3D api. While not required (we’ll start from scratch), you might want to read the previous tutorials prior to this one, if you haven’t done so. Especially the previous tutorials frustum culling, ray picking and collision shapes are leading into collision detection.

This is a two part tutorial. In this first part we’ll look at how to setup the Bullet wrapper and use it for basic collision detection. In the second part we’ll look at rigid body dynamics. Since I think that’s important to have some basic knowledge of what happens behind the scenes, I’ll show you what actually happens when you perform collision detection and how you can use the Bullet wrapper to maintain performance.

Create a basic 3D test scene

So, let’s start coding! You can go ahead and create a new LibGDX project, I assume you’re familiar with that and will not walk you through it. If you use the setup, you can add the gdx-bullet extension as well. If not, you’ll have to manually add it later. When you’re all setup, create a class to be the ApplicationListener:

public class BulletTest implements ApplicationListener {

@Override public void create () {}

@Override public void render () {}

@Override public void dispose () {}

@Override public void pause () {}

@Override public void resume () {}

@Override public void resize (int width, int height) {}

}

Now add the basics that we need for our 3D test, like a camera, camera controller, model batch and environment.

public class BulletTest implements ApplicationListener {

PerspectiveCamera cam;

CameraInputController camController;

ModelBatch modelBatch;

Array<ModelInstance> instances;

Environment environment;

@Override

public void create () {

modelBatch = new ModelBatch();

environment = new Environment();

environment.set(new ColorAttribute(ColorAttribute.AmbientLight, 0.4f, 0.4f, 0.4f, 1f));

environment.add(new DirectionalLight().set(0.8f, 0.8f, 0.8f, -1f, -0.8f, -0.2f));

cam = new PerspectiveCamera(67, Gdx.graphics.getWidth(), Gdx.graphics.getHeight());

cam.position.set(3f, 7f, 10f);

cam.lookAt(0, 4f, 0);

cam.update();

camController = new CameraInputController(cam);

Gdx.input.setInputProcessor(camController);

instances = new Array<ModelInstance>();

}

@Override

public void render () {

camController.update();

Gdx.gl.glClearColor(0.3f, 0.3f, 0.3f, 1.f);

Gdx.gl.glClear(GL20.GL_COLOR_BUFFER_BIT | GL20.GL_DEPTH_BUFFER_BIT);

modelBatch.begin(cam);

modelBatch.render(instances, environment);

modelBatch.end();

}

@Override

public void dispose () {

modelBatch.dispose();

}

@Override public void pause () {}

@Override public void resume () {}

@Override public void resize (int width, int height) {}

}

If any of this is new to you, you might want to read this tutorial first.

Time to add some visual objects which we will use for the collision detection.

public class BulletTest implements ApplicationListener {

...

Model model;

ModelInstance ground;

ModelInstance ball;

@Override

public void create () {

...

camController = new CameraInputController(cam);

Gdx.input.setInputProcessor(camController);

ModelBuilder mb = new ModelBuilder();

mb.begin();

mb.node().id = "ground";

mb.part("box", GL20.GL_TRIANGLES, Usage.Position | Usage.Normal, new Material(ColorAttribute.createDiffuse(Color.RED)))

.box(5f, 1f, 5f);

mb.node().id = "ball";

mb.part("sphere", GL20.GL_TRIANGLES, Usage.Position | Usage.Normal, new Material(ColorAttribute.createDiffuse(Color.GREEN)))

.sphere(1f, 1f, 1f, 10, 10);

model = mb.end();

ground = new ModelInstance(model, "ground");

ball = new ModelInstance(model, "ball");

ball.transform.setToTranslation(0, 9f, 0);

instances = new Array<ModelInstance>();

instances.add(ground);

instances.add(ball);

}

...

@Override

public void dispose () {

modelBatch.dispose();

model.dispose();

}

...

}

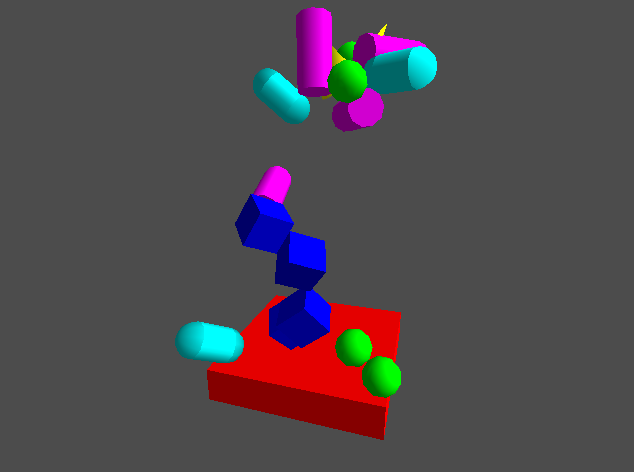

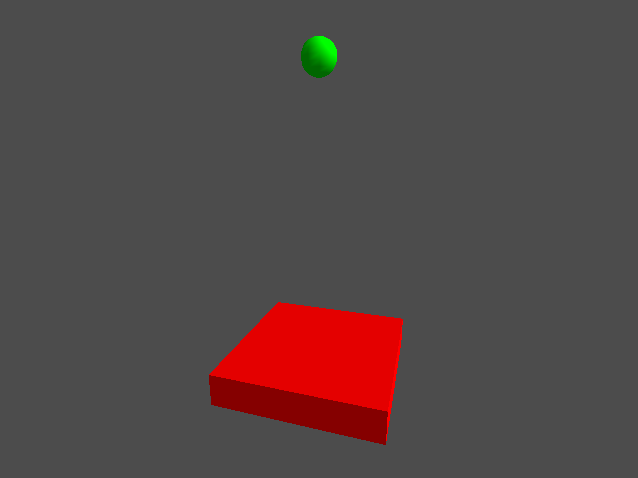

Here I used ModelBuilder to create a model with two nodes. One called “ground” and one called “ball” (read this tutorial if you want to know more about nodes). Next we create a ModelInstance of each Node (as described in this tutorial) and we move the ball a little above the ground. If you run this, it will look something like this:

Now we’re going to move the ball downwards until it collides with the ground. For now, we’ll use a method stub for the actual collision detection:

public class BulletTest implements ApplicationListener {

...

boolean collision;

...

@Override

public void render () {

final float delta = Math.min(1f/30f, Gdx.graphics.getDeltaTime());

if (!collision) {

ball.transform.translate(0f, -delta, 0f);

collision = checkCollision();

}

...

}

boolean checkCollision() {

return false;

}

...

}

View full source code on Github

We added a flag called collision, as long as this flag isn’t set we move the ball downwards with one unit (e.g. meter) per second. For this we use the Gdx.graphics.getDeltaTime() methods, which gives us the time (in seconds) since the last time the render method was called. Math.min is used to limit this time to a maximum. This avoids “teleportation”, e.g. when for some reason a hick-up occurs.

If you run this, you’ll see that ball will simply fall through the ground and won’t stop.

Detecting if the ball and ground collide

Time to add some actual collision detection. If you haven’t done so already, make sure to add the gdx-bullet extension to your project. You can do this with the LibGDX setup by clicking the bullet extension checkbox. If you prefer, you can also manually add the extension (e.g. by adding the jar to the java build path and the .so files to the android libs folder).

The first thing to remember about the Bullet wrapper is that you can never use the wrapper before it is initialized. This can be done using the static method Bullet.init();:

@Override

public void create () {

Bullet.init();

...

}

It might seem obvious that you can’t use the wrapper before it is initialized, but keep in mind that (static) members are initialized before the create method is called. For example (pseudo code):

SomeBulletClass member = new SomeBulletClass();

or (pseudo code):

SomeBulletCallback callback = new SomeBulletCallback() {

public void theCallback() {

...

}

}

will not work, because the code (the constructor) is called before the call to Bullet.init(); is executed. Therefor make sure that you always construct any Bullet related objects after the Bullet wrapper is initialized.

If you added above line (Bullet.init();), you probably want to run the project to make sure that the library is initialized successfully. If for some reason the library (e.g. on windows the DLL file) can’t be loaded an exception will be thrown. In that case check your project configuration or try to recreate the project using the libgdx setup utility.

Before we can check if the ball collides with the ground, we need to specify the shape of both objects. If you’ve read the previous tutorial you’re already familiar with collision shapes. Bullet provides many collision shapes. Ranging from primitive shapes, like box, sphere, cylinder, cone and capsule, to a more general convex shape, an optimized convex hull shape, mesh shape and any combination of those. For now, a simple box and sphere should be enough for our test:

public class BulletTest implements ApplicationListener {

...

btCollisionShape groundShape;

btCollisionShape ballShape;

@Override

public void create () {

Bullet.init();

...

ballShape = new btSphereShape(0.5f);

groundShape = new btBoxShape(new Vector3(2.5f, 0.5f, 2.5f));

}

...

}

btCollisionShape is the base class of every shape. For the ball we create a btSphereShape, which takes the radius as argument. The diameter of the ball is 1 unit, thus the radius is 0.5f. For the ground we create a btBoxShape, which takes the half extents as arguments. Since the ground is 5 units wide, 1 unit in height and has a depth of 5 units, we need to provide half of those values. This is done using a Vector3.

Note that Vector3 is a LibGDX class. Bullet’s equivalent is btVector3 (which is also available in the wrapper). Where possible, the wrapper will bridge between LibGDX’s math classes and the Bullet math classes. It will even do some optimizations for you when doing so (more on this later).

A collision shape isn’t enough to do collision detection. We will need to inform Bullet about the location (and rotation) of each shape. This is done using a collision object:

public class BulletTest implements ApplicationListener {

...

btCollisionObject groundObject;

btCollisionObject ballObject;

@Override

public void create () {

...

groundObject = new btCollisionObject();

groundObject.setCollisionShape(groundShape);

groundObject.setWorldTransform(ground.transform);

ballObject = new btCollisionObject();

ballObject.setCollisionShape(ballShape);

ballObject.setWorldTransform(ball.transform);

}

@Override

public void render () {

...

if (!collision) {

ball.transform.translate(0f, -delta, 0f);

ballObject.setWorldTransform(ball.transform);

collision = checkCollision();

}

...

}

...

}

As you can see, a collision object is simply the combination of a collision shape and its transform. The transform in this case is its position and rotation. Just like we did with Vector3 for the box shape, we can set the transform using the transform member of the ModelInstance. The wrapper translates this Matrix4 for us to bullet’s equivalent btTransform. While this is easy to work with, you should keep in mind that the transform -as far as bullet is concerned- only contains a position and rotation. Any other transformation, like for example scaling, is not supported. In practice this means that you should never apply scaling directly to objects when using the bullet wrapper. There are other ways to scale objects, but in general I would recommend to try to avoid scaling.

Now we’ve got the two objects and we want to detect if they collide. Before we can start the actual collision detection we need a few helper classes.

public class BulletTest implements ApplicationListener {

...

btCollisionConfiguration collisionConfig;

btDispatcher dispatcher;

@Override

public void create () {

...

collisionConfig = new btDefaultCollisionConfiguration();

dispatcher = new btCollisionDispatcher(collisionConfig);

}

...

}

We will look at the importance of these objects later, for now just make sure to construct them in the create method.

By now, you probably also noticed that until now all bullet classes start with the prefix “bt”. While that’s not always the true, it is most in cases.

Every time you construct a bullet class in java, the wrapper will also construct the same class in the native (C++) library. But while in java the garbage collector takes care of memory management and will free an object when you don’t use it anymore, in C++ you’re responsible for freeing the memory yourself. You’re probably already familiar with this cconcept, because the same goes for a texture, model, model batch, shader etc. Because of this, you have to manually dispose the object when you no longer need it.

@Override

public void dispose () {

groundObject.dispose();

groundShape.dispose();

ballObject.dispose();

ballShape.dispose();

dispatcher.dispose();

collisionConfig.dispose();

modelBatch.dispose();

model.dispose();

}

We already disposed the model batch and model in the dispose method. Now, we’ve also disposed the collision shapes, collision objects and the helper classes dispatcher and collisionConfig which we’ll look at soon.

Now we can start implementing the checkCollision method. Basically what we want is to check if the sphere collides with the box. Bullet has an algorithm for just that, called btSphereBoxCollisionAlgorithm.

boolean checkCollision() {

CollisionObjectWrapper co0 = new CollisionObjectWrapper(ballObject);

CollisionObjectWrapper co1 = new CollisionObjectWrapper(groundObject);

btCollisionAlgorithmConstructionInfo ci = new btCollisionAlgorithmConstructionInfo();

ci.setDispatcher1(dispatcher);

btCollisionAlgorithm algorithm = new btSphereBoxCollisionAlgorithm(null, ci, co0.wrapper, co1.wrapper, false);

btDispatcherInfo info = new btDispatcherInfo();

btManifoldResult result = new btManifoldResult(co0.wrapper, co1.wrapper);

algorithm.processCollision(co0.wrapper, co1.wrapper, info, result);

boolean r = result.getPersistentManifold().getNumContacts() > 0;

result.dispose();

info.dispose();

algorithm.dispose();

ci.dispose();

co1.dispose();

co0.dispose();

return r;

}

View full source code on Github

The first thing we do here is create a CollisionObjectWrapper for each object. Note that this class doesn’t start with the prefix “bt”, which is because it is a class specific to the libgdx bullet wrapper (it wraps a btCollisionObjectWrapper object, which can be accessed through the wrapper member).

Next we construct a btCollisionAlgorithmConstructionInfo instance, which is used to specify information about the collision algorithm we want to create. We’ll keep things default and because it needs a btDispatcher we just feed it the dispatcher that we created earlier.

After that we construct a btSphereBoxCollisionAlgorithm, which needs the objects that we just created as arguments for the constructor. This is the algorithm that we’ll be using to check if the sphere collides with the box. To execute this algorithm we need an additional btDispatcherInfo (which provides additional information about the desired algorithm) and a btManifoldResult (which will receive the result). Note that the algorithm is an instance of btCollisionAlgorithm which is the super class of all collision algorithms.

Now we can actually execute the algorithm by calling the processCollision method of the algorithm. This will store the result (the contact points) in the btManifoldResult we’ve create earlier. If the number of contact points is more than zero, then there’s a collision.

Finally, like we’ve seen earlier, it is important to dispose every bullet class that we’ve constructor.

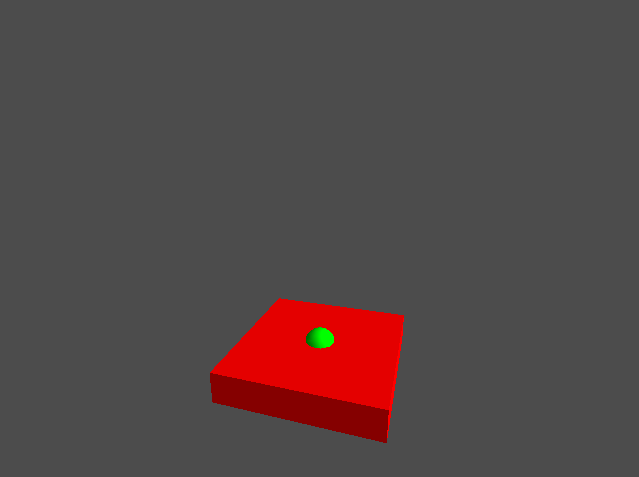

If you run this, you’ll see that it does exactly what we wanted. The ball will stop moving when it hits the ground.

If this seems a bit overwhelming, don’t worry, it will get clear later on. For now make sure that you understand the basics of what we just did: We’ve created two collision shapes. Then created two collision objects containing a shape, position and rotation. To check if the two objects collide, we’ve create a collision algorithm which is specifically designed for detecting sphere-box collisions. The result of this collision detection is called a manifold, which contains the contact points (if any) of the collision. These contact points contain information over the collision, for example the distance (penetration) and direction of the collision.

A peek behind the scenes

Before we continue, I think this is a good moment to see what is actually going on behind the scenes. Let’s have a quick look at the following line:

boolean r = result.getPersistentManifold().getNumContacts() > 0;

What this basically does is exactly the same as:

btPersistentManifold manifold = result.getPersistentManifold();

int numContacts = manifold.getNumContacts();

boolean r = (numContacts > 0);

The call to result.getPersistentManifold() returns a btPersistentManifold. Now let’s have a small peek at what the wrapper has to do behind the scenes for this:

public btPersistentManifold getPersistentManifold() {

long cPtr = CollisionJNI.btManifoldResult_getPersistentManifold__SWIG_0(swigCPtr, this);

return (cPtr == 0) ? null : new btPersistentManifold(cPtr, false);

}

Don’t worry, you don’t need to understand exactly what’s going on here. But I think that it is good practice that you have some global understanding of the impact of the code that you’re writing. In the first line the wrapper executes the method (getPersistentManifold) on the native (C++) object. The result of this method is a long value. This value is the “pointer” to the btPersistentManifold object in the C++ library. A pointer is simply the location in memory where the object resides. This long value can later be used to execute methods on the btPersistentManifold object.

On the next line the wrapper creates the java equivalent of the btPersistentManifold object, so you can easily use it. All java bullet classes contain the pointer to the equivalent C++ class. You can access this long value using the getCPointer() method that every java bullet class has.

Note that because we didn’t explicitly created the btPersistentManifold object (or in other words: we don’t own it), we also don’t have to dispose the object. However, it doesn’t harm if you do dispose it, the wrapper knows that we don’t own it and will therefor not destroy the backing C++ object. You can query the ownership of each java bullet class, using the hasOwnership() method.

Using the collision dispatcher

Back to our collision detection test. As you probably can imagine there are many collision algorithms, for each possible pair of collision objects (shapes) there’s a collision algorithm. Manually creating a collision algorithm for each collision pair will get messy really fast. Luckily Bullet can create a collision algorithm for each pair of objects for us. This is done by the dispatcher which we’ve created earlier.

@Override

public void render () {

...

collision = checkCollision(ballObject, groundObject);

...

}

boolean checkCollision(btCollisionObject obj0, btCollisionObject obj1) {

CollisionObjectWrapper co0 = new CollisionObjectWrapper(obj0);

CollisionObjectWrapper co1 = new CollisionObjectWrapper(obj1);

btCollisionAlgorithm algorithm = dispatcher.findAlgorithm(co0.wrapper, co1.wrapper);

btDispatcherInfo info = new btDispatcherInfo();

btManifoldResult result = new btManifoldResult(co0.wrapper, co1.wrapper);

algorithm.processCollision(co0.wrapper, co1.wrapper, info, result);

boolean r = result.getPersistentManifold().getNumContacts() > 0;

dispatcher.freeCollisionAlgorithm(algorithm.getCPointer());

result.dispose();

info.dispose();

co1.dispose();

co0.dispose();

return r;

}

View full source code on Github

I’ve modified the checkCollision signature a bit so that it can be used for any pair of collision objects. Instead of manually creating a sphere-box collision algorithm, we now ask the dispatcher to find the correct algorithm for us using the dispatcher.findAlgorithm method. The rest of the method is pretty much the same as before. Except for one thing: we don’t own the algorithm anymore, so we don’t have to dispose it anymore. Instead we need to inform the dispatcher that we’re done with the algorithm so that it can be reused (pooled) for other collision detection. For this the dispatcher needs to now the location in memory of the algorithm. As we’ve seen earlier, we can use the getCPointer method to get this location.

Add more objects

Well that’s nice, we now have a generic method to check if two objects intersect. So let’s add some additional objects that we can compare against each other. And while we’re at it, we might as well make the code a bit cleaner for using multiple objects. Therefor, first add the collision object to the model instance by extending the ModelInstance class:

public class BulletTest implements ApplicationListener {

static class GameObject extends ModelInstance implements Disposable {

public final btCollisionObject body;

public boolean moving;

public GameObject(Model model, String node, btCollisionShape shape) {

super(model, node);

body = new btCollisionObject();

body.setCollisionShape(shape);

}

@Override

public void dispose () {

body.dispose();

}

}

...

}

By having a btCollisionObject body member (which basically is the collision shape and transformation), it is easier to maintain our game objects. We will use the moving member to decide if the object is on the ground or not.

Another nice way to make the code a bit cleaner is to use “factory” classes:

public class BulletTest implements ApplicationListener {

static class GameObject extends ModelInstance implements Disposable {

...

static class Constructor implements Disposable {

public final Model model;

public final String node;

public final btCollisionShape shape;

public Constructor(Model model, String node, btCollisionShape shape) {

this.model = model;

this.node = node;

this.shape = shape;

}

public GameObject construct() {

return new GameObject(model, node, shape);

}

@Override

public void dispose () {

shape.dispose();

}

}

}

}

Now we can have a GameObject.Constructor for each different shape and call the construct method on it to create a GameObject. If you combine this with a map, you get a really convenient method to construct your game objects:

public class BulletTest implements ApplicationListener {

...

Array<GameObject> instances;

ArrayMap<String, GameObject.Constructor> constructors;

@Override

public void create () {

...

camController = new CameraInputController(cam);

Gdx.input.setInputProcessor(camController);

ModelBuilder mb = new ModelBuilder();

mb.begin();

mb.node().id = "ground";

mb.part("ground", GL20.GL_TRIANGLES, Usage.Position | Usage.Normal, new Material(ColorAttribute.createDiffuse(Color.RED)))

.box(5f, 1f, 5f);

mb.node().id = "sphere";

mb.part("sphere", GL20.GL_TRIANGLES, Usage.Position | Usage.Normal, new Material(ColorAttribute.createDiffuse(Color.GREEN)))

.sphere(1f, 1f, 1f, 10, 10);

mb.node().id = "box";

mb.part("box", GL20.GL_TRIANGLES, Usage.Position | Usage.Normal, new Material(ColorAttribute.createDiffuse(Color.BLUE)))

.box(1f, 1f, 1f);

mb.node().id = "cone";

mb.part("cone", GL20.GL_TRIANGLES, Usage.Position | Usage.Normal, new Material(ColorAttribute.createDiffuse(Color.YELLOW)))

.cone(1f, 2f, 1f, 10);

mb.node().id = "capsule";

mb.part("capsule", GL20.GL_TRIANGLES, Usage.Position | Usage.Normal, new Material(ColorAttribute.createDiffuse(Color.CYAN)))

.capsule(0.5f, 2f, 10);

mb.node().id = "cylinder";

mb.part("cylinder", GL20.GL_TRIANGLES, Usage.Position | Usage.Normal, new Material(ColorAttribute.createDiffuse(Color.MAGENTA)))

.cylinder(1f, 2f, 1f, 10);

model = mb.end();

constructors = new ArrayMap<String, GameObject.Constructor>(String.class, GameObject.Constructor.class);

constructors.put("ground", new GameObject.Constructor(model, "ground", new btBoxShape(new Vector3(2.5f, 0.5f, 2.5f))));

constructors.put("sphere", new GameObject.Constructor(model, "sphere", new btSphereShape(0.5f)));

constructors.put("box", new GameObject.Constructor(model, "box", new btBoxShape(new Vector3(0.5f, 0.5f, 0.5f))));

constructors.put("cone", new GameObject.Constructor(model, "cone", new btConeShape(0.5f, 2f)));

constructors.put("capsule", new GameObject.Constructor(model, "capsule", new btCapsuleShape(.5f, 1f)));

constructors.put("cylinder", new GameObject.Constructor(model, "cylinder", new btCylinderShape(new Vector3(.5f, 1f, .5f))));

instances = new Array<GameObject>();

instances.add(constructors.get("ground").construct());

collisionConfig = new btDefaultCollisionConfiguration();

dispatcher = new btCollisionDispatcher(collisionConfig);

}

...

@Override

public void dispose () {

for (GameObject obj : instances)

obj.dispose();

instances.clear();

for (GameObject.Constructor ctor : constructors.values())

ctor.dispose();

constructors.clear();

dispatcher.dispose();

collisionConfig.dispose();

modelBatch.dispose();

model.dispose();

}

}

As you can see I’ve removed the previous code to construct the collision shapes and objects and replaced it to using the GameObject.Constructor class. The instances array is now an array of GameObject instances. We use the ModelBuilder to create the nodes for each shape. Next we create a GameObject.Constructor for each shape, including the btCollisionShape for each constructor. We’ve given each constructor a descriptive name in the map, so that you now can create a game object like this: constructors.get(name).construct(). Of course we need to dispose each collision object and shape just like before, therefor the dispose method is modified a bit as well.

Now let’s modify the render method to use the GameObject and make it add a new game object every second or so:

public class BulletTest implements ApplicationListener {

...

float spawnTimer;

...

@Override

public void render () {

final float delta = Math.min(1f/30f, Gdx.graphics.getDeltaTime());

for (GameObject obj : instances) {

if (obj.moving) {

obj.transform.trn(0f, -delta, 0f);

obj.body.setWorldTransform(obj.transform);

if (checkCollision(obj.body, instances.get(0).body))

obj.moving = false;

}

}

if ((spawnTimer -= delta) < 0) {

spawn();

spawnTimer = 1.5f;

}

...

}

public void spawn() {

GameObject obj = constructors.values[1+MathUtils.random(constructors.size-2)].construct();

obj.moving = true;

obj.transform.setFromEulerAngles(MathUtils.random(360f), MathUtils.random(360f), MathUtils.random(360f));

obj.transform.trn(MathUtils.random(-2.5f, 2.5f), 9f, MathUtils.random(-2.5f, 2.5f));

obj.body.setWorldTransform(obj.transform);

instances.add(obj);

}

...

}

View full source code on Github

For each GameObject we check if it is moving and if so move it downwards with one unit per second. Then we check if it collides with the first game object (which we know is the ground) and if so, we stop moving the object. Next we use a member spawnTimer to call the spawn() method every 1.5 seconds.

In the spawn method we randomly construct a new GameObject (except for the floor) and set it to a random location above the ground. We also rotate it randomly. And because the object is rotated now we use the trn method instead of the translate method to translate the object. The trn method will translate the object regardless rotation, so the object will always move towards the location we specify.

I’m not going into the details of these changes, because they aren’t Bullet related and should be straight forward. All we did was make our code a bit cleaner for multiple game objects.

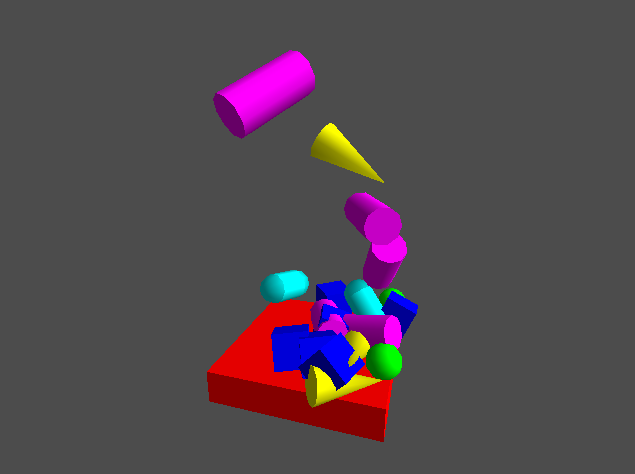

If you run this, you’ll see various random object falling onto the ground:

Using a ContactListener

All of this is nice if you want to check if two objects collide. But if we also want to check if the objects collide with each other and the number of objects grows, this will get messy and slow. Instead of checking each possible collision pair, it’s much more convenient to get notified when a collision occurs. Luckily Bullet offers callback methods which will be called on certain collision events.

public class BulletTest implements ApplicationListener {

class MyContactListener extends ContactListener {

@Override

public boolean onContactAdded (btManifoldPoint cp, btCollisionObjectWrapper colObj0Wrap, int partId0, int index0,

btCollisionObjectWrapper colObj1Wrap, int partId1, int index1) {

instances.get(colObj0Wrap.getCollisionObject().getUserValue()).moving = false;

instances.get(colObj1Wrap.getCollisionObject().getUserValue()).moving = false;

return true;

}

}

...

MyContactListener contactListener;

@Override

public void create () {

...

contactListener = new MyContactListener();

}

@Override

public void render () {

...

for (GameObject obj : instances) {

if (obj.moving) {

obj.transform.trn(0f, -delta, 0f);

obj.body.setWorldTransform(obj.transform);

checkCollision(obj.body, instances.get(0).body);

}

}

...

}

public void spawn() {

...

obj.body.setUserValue(instances.size);

obj.body.setCollisionFlags(obj.body.getCollisionFlags() | btCollisionObject.CollisionFlags.CF_CUSTOM_MATERIAL_CALLBACK);

...

}

...

@Override

public void dispose () {

...

contactListener.dispose();

...

}

View full source code on Github

Here we create a ContactListener, which is not a Bullet class, but a class specifically created for the wrapper. Bullet doesn’t use object oriented callbacks for collision events, all callbacks are global methods (a bit comparable static java methods). Because it’s not possible in Java to use global callback methods, the wrapper adds the ContactListener class to take care of that. This is also the reason that we don’t have to inform bullet to use our ContactListener, the wrapper takes care of that when you construct the ContactListener.

The onContactAdded method is called whenever a contact point is added to a manifold. As we’ve seen earlier, as soon as a manifold has one or more contact points, there’s a collision. So basically this method is called when a collision occurs between two objects.

Of course the Bullet library isn’t aware of our GameObject class, so we need a way to get our GameObject using the data Bullet provides to us in the callback method. If you’re familiar with box2d, you’re probably also familiar with using a userData member for that. The Bullet wrapper also supports a userData member of the btCollisionObject which is practically the same. However, we’ll use the setUserValue and getUserValue methods instead. This is an integer value which we set to the index of the GameObject in the instances array. So, using instances.get(colObj0Wrap.getCollisionObject().getUserValue()) we can get the corresponding GameObject.

In the spawn method we set this value, using the setUserValue method, to the index of the object in the instances array. And we also inform Bullet that we want to receive collision events for this object by adding the CF_CUSTOM_MATERIAL_CALLBACK flag. This flag is required for the onContactAdded method to be called.

In the render method we now don’t have to set the moving flag anymore, so I removed that part and only call the checkCollision method. Like always the contactListener has to be disposed, so we’ve added a line to the dispose method.

If you run this, you’ll see it does exactly the same as before, but now we use contact callback instead of polling each collision pair.

Optimizing frequently called methods

Earlier we’ve seen that all wrapper classes are basically a pointer to the corresponding C++ object. This is how the wrapper can call the appropriate method on the C++ object when you call a method on a java object. But that’s only a one-way street. How is it possible that the Bullet C++ code invokes a Java method? Well, for most classes it isn’t. Only for classes specifically designed to be extended the overridden methods will be called. This is to reduce the overhead of bridging from C++ to Java, so that no performance is lost when a method is not intended to be overridden. ContactListener is such a class which is intended to be overridden and there are quite a few other “callback” classes as well.

As we’ve seen earlier, the wrapper will create a java object for each C++ object as we need it. Creating objects when we don’t need them is of course (and especially for games) something we want to avoid. Because of this, the wrapper lets you specify which objects you really need inside the ContactListener methods. For this the ContactListener has multiple signatures of the same method which you can override. You can only override one of those, because the wrapper will only call one method for an event.

Looking at our ContactListener, we never use the btManifoldPoint. So if we use the signature which doesn’t include that argument, then the wrapper doesn’t have to create it:

class MyContactListener extends ContactListener {

@Override

public boolean onContactAdded (btCollisionObjectWrapper colObj0Wrap, int partId0, int index0,

btCollisionObjectWrapper colObj1Wrap, int partId1, int index1) {

instances.get(colObj0Wrap.getCollisionObject().getUserValue()).moving = false;

instances.get(colObj1Wrap.getCollisionObject().getUserValue()).moving = false;

return true;

}

}

Because a btCollisionObjectWrapper is frequently used in a callback, the wrapper takes special care of that. It uses a pool for those objects. But since we don’t actually use the btCollisionObjectWrapper and only need the btCollisionObject that it wraps, we might as well use the method signature that provides a btCollisionObject instead.

class MyContactListener extends ContactListener {

@Override

public boolean onContactAdded (btCollisionObject colObj0, int partId0, int index0, btCollisionObject colObj1, int partId1,

int index1) {

instances.get(colObj0.getUserValue()).moving = false;

instances.get(colObj1.getUserValue()).moving = false;

return true;

}

}

Since a btCollisionObject is always created in Java, the wrapper will make sure to use that instance every time it needs to. For this it uses a long-map (with the C++ pointer as key). Of course there’s a small overhead of looking up the correct btCollisionObject, but this allows you to extend btCollisionObject and make sure you will always have access to the extended class in the callbacks.

However, we only need the user value in the callback, this value is enough to locate the GameObject in the instances array. We don’t need the wrapper to look-up the collision object using the long-map.

class MyContactListener extends ContactListener {

@Override

public boolean onContactAdded (int userValue0, int partId0, int index0, int userValue1, int partId1, int index1) {

instances.get(userValue0).moving = false;

instances.get(userValue1).moving = false;

return true;

}

}

View full source code on Github

The wrapper has the ability of providing us the userValue, and therefor completely eliminating the need to create an object at all. We’ve now created a callback method with only primitive arguments, which means that there will be no objects created or map look-ups for this method call.

Add a collision world

Now we receive an event when there’s a collision, but we are still manually checking each object if it collides with the ground. And while the method we use to check for collision works pretty well, it is far from optimized. First of all, we are constructing and destroying quite some objects in the checkCollision method. And as we’ve just seen, it’s best to prevent creating objects frequently. Otherwise the garbage collector might cause a hick-up every few seconds or so.

But even besides the fact that we construct many objects, there’s another issue. We’re using a specialized collision algorithm every time. And as you might remember from the previous tutorial, specialized collision algorithms can be relatively expensive. Ideally we’d first check if the two objects are near each other, for example using a bounding box or bounding sphere. And only if they are near each other, we’d use the more accurate specialized collision algorithm.

Using such two phase collision detection has many benefits. The first phase, where we find collision objects that are near each other, is called the broad phase. Then the second phase, where a more accurate specialized collision algorithm is used, is called the near phase. Up until now we’ve only looked at the near phase. In practice the collision dispatcher is the class we’ve used for the near phase.

As you can imagine, in a common scenario the broad phase is called for all collision objects, while the near phase is only called for a few objects. It’s therefor crucial that the broad phase is highly optimized. Bullet does this by caching the collision information, so it doesn’t have to recalculate it every time. There are several implementations you can choose from, but in practice this is done in the form a tree. I’ll not go into detail about this, but if you want to know more about it, you can search for “axis aligned bounding box tree” or in short “AABB tree”.

The term “AABB” is quite often used in collision detection (in relation to the broad phase). This simply refers to the bounding box, just like we’ve used in the previous few tutorials. The bounds only consist of a location (the center) and it’s dimensions. It doesn’t contain rotation, which makes it very easy (and cheap) to check if two bounding boxes overlap.

Of course the tree has to be stored somewhere and updated when an object is added, removed or transformed. Luckily Bullet provides a nice class which does this all for us, called a collision world. Basically you tell the world which broad phase and near phase you want to use, next you can add, remove or transform collision objects and the collision world will notify you (through the ContactListener) when a collision occurs. Let’s add a collision world, including a broad phase:

public class BulletTest implements ApplicationListener {

...

btBroadphaseInterface broadphase;

btCollisionWorld collisionWorld;

@Override

public void create () {

...

collisionConfig = new btDefaultCollisionConfiguration();

dispatcher = new btCollisionDispatcher(collisionConfig);

broadphase = new btDbvtBroadphase();

collisionWorld = new btCollisionWorld(dispatcher, broadphase, collisionConfig);

contactListener = new MyContactListener();

instances = new Array<GameObject>();

GameObject object = constructors.get("ground").construct();

instances.add(object);

collisionWorld.addCollisionObject(object.body);

}

public void spawn () {

...

instances.add(obj);

collisionWorld.addCollisionObject(obj.body);

}

@Override

public void render () {

final float delta = Math.min(1f / 30f, Gdx.graphics.getDeltaTime());

for (GameObject obj : instances) {

if (obj.moving) {

obj.transform.trn(0f, -delta, 0f);

obj.body.setWorldTransform(obj.transform);

}

}

collisionWorld.performDiscreteCollisionDetection();

...

}

// Remove the checkCollision method, it's no longer needed

@Override

public void dispose () {

...

collisionWorld.dispose();

broadphase.dispose();

...

}

...

}

View full source code on Github

Here we create btBroadphaseInterface and btCollisionWorld. For the broad phase I’ve chosen the btDbvtBroadphase implementation, which is a dynamic bounding volume tree implementation. In most scenario’s this implementation should suffice. Next we need to add the ground and other objects that we create in the spawn method to the collision world, using the collisionWorld.addCollisionObject method. I’ve removed the checkCollision method, instead we now call collisionWorld.performDiscreteCollisionDetection();. This method will check for collision between all objects that we’ve added to the world and will call the ContactListener when there’s a collision.

Well that’s nice, we now don’t have to create any object to detect the collision, so the garbage collection will not kick in. Also, if you look at the actual bullet related code, you’ll see that it is just a few lines of code. Most of the code we created, is related to rendering and managing game objects.

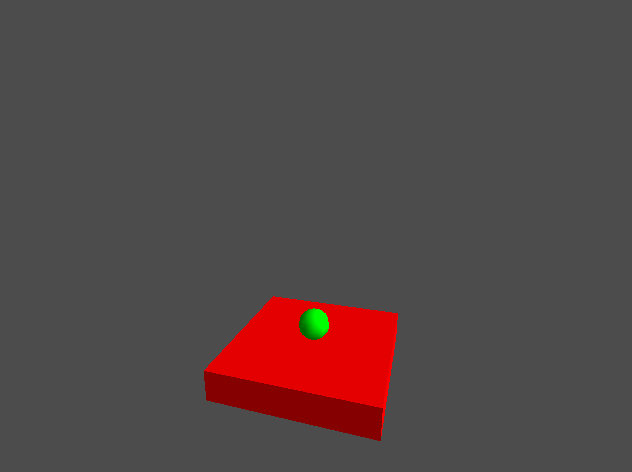

If you run this, you’ll see that it does the same as before… sort of:

Collision filtering

Because the world detects collision between all objects and not only the ground, the objects now also stop moving when they collide to each other. It shouldn’t be too hard to fix that:

class MyContactListener extends ContactListener {

@Override

public boolean onContactAdded (int userValue0, int partId0, int index0, int userValue1, int partId1, int index1) {

if (userValue1 == 0)

instances.get(userValue0).moving = false;

else if (userValue0 == 0)

instances.get(userValue1).moving = false;

return true;

}

}

We know that the ground has a userValue of zero. We now check if one of the objects that collide is the ground and if so, we stop moving the other object. Because it is possible that either of the objects is the ground, we need to check both values.

While that works for our test, it’s not a very generic solution. Even more, the world still has to perform both the broad phase and near phase collision detection on the pairs that we want to ignore. It would be better to tell the world that it can simply ignore the objects against each other and only has to check for each object if it collides with the ground. One very efficient way to do this, is using collision flags:

public class BulletTest implements ApplicationListener {

final static short GROUND_FLAG = 1<<8;

final static short OBJECT_FLAG = 1<<9;

final static short ALL_FLAG = -1;

...

@Override

public void create () {

...

collisionWorld.addCollisionObject(object.body, GROUND_FLAG, ALL_FLAG);

}

public void spawn () {

...

collisionWorld.addCollisionObject(obj.body, OBJECT_FLAG, GROUND_FLAG);

}

View full source code on Github

Here we created three flags. The first one GROUND_FLAG has only the ninth bit set. The second one OBJECT_FLAG has only the tenth bit set. The last one ALL_FLAG has all bits set. Next, when adding the ground to the world, we tell Bullet which flag to use for this particular object and to which objects the object can collide. So the ground collides will all objects. When spawning an object we tell Bullet that the object should only collide with the ground. Bullet uses a bitwise comparison to check if it should detect collision between two objects. If you’re unfamiliar with bitwise comparison, I’d advise to read into it, it is a very useful and fast method, not only for collision filtering.

So, why did I start at the ninth bit and not the first? The answer is: just to be safe. Bullet uses internally a few bits, as described here. While this doesn’t have to be a problem, it’s generally better to use bits which aren’t used for anything else. Note that the flags are short values, so the bits are relatively scarce, it is advised to choose them carefully.

What’s next

This concludes this first part on using the LibGDX Bullet wrapper. In the next part we’ll look at rigid body dynamics, where we’ll use Bullet for full physics simulation. For example applying forces/gravity and let objects interact with each other.

Of course, it’s impossible to cover every aspect of collision detection in this tutorial. For example, it is possible to use Bullet for more accurate ray picking, than we’ve seen in the previous tutorial. You could even use Bullet for frustum culling (although that’s not advised).

I highly suggest to read the Bullet manual, it is a good read and the place to start when using the Bullet library. It isn’t targeted to the LibGDX Bullet wrapper, but of it still applies.

The Bullet website and especially the Bullet wiki provides a lot of practical information, for example about the various collision shapes, contact callbacks and collision filtering. Also the forum is quite active.

This wiki page provides a lot of information specifically for the LibGDX Bullet wrapper.

This webpage is open source and can be found at: https://github.com/xoppa/xoppa.github.io.

The accompanying sources can be found at: https://github.com/xoppa/blog.

Let me know what you think about this post in the comments below. If you need help then please use the forum instead. If you found an issue with this post then please report an issue or send a pull request.