A very common mistake when creating a (2D) game is to use (imaginary) pixels. Although it’s certainly understandable that some might find it easier to “think in pixels” when creating a 2D game, especially when learning, it is doomed to cause issues on the long run. In this little blog post I will show you why there are no pixels and why you probably shouldn’t use them.

Please note that in the first part of this post I will show you bad practice code as an example. Do not use this code in an actual project.

I’m using libGDX in this post to show you why pixels are bad and I assume you’re already somewhat familiar with libGDX. A typical minimal libGDX ApplicationListener could look like this:

public class LibGDXTest extends ApplicationAdapter {

SpriteBatch batch;

Texture texture;

public void create () {

batch = new SpriteBatch();

texture = new Texture(Gdx.files.internal("data/badlogic.jpg"));

}

public void render () {

Gdx.gl.glClear(GL20.GL_COLOR_BUFFER_BIT);

batch.begin();

batch.draw(texture, 0, 0);

batch.end();

}

public void dispose () {

texture.dispose();

batch.dispose();

}

}

This creates a SpriteBatch and a Texture and then render the texture using the spritebatch, which looks a bit like this:

Although the actual result might be different depending on the resolution of the device. The texture (the image file “data/badlogic.jpg”) in this case is 256 by 256 pixels. The screen in this case is around 640 (width) by 480 (height) pixels. This is called “pixel perfect”, which means that every pixel of the rendered texture on the screen matches with a pixel on the source texture.

Unfortunately this isn’t very useful for most games, because devices can vary in resolution. You don’t want your gameplay to be different depending on the device resolution. To solve this, quite often a virtual resolution is used. This is a fixed resolution at which the game is designed. If the device the game is played on actually has a different resolution, then it is scaled to fit. Commonly this is done using an OrthographicCamera or a Viewport (the latter encapsulates the camera):

public class LibGDXTest extends ApplicationAdapter {

final float VIRTUAL_WIDTH = 1280; // +++

final float VIRTUAL_HEIGHT = 720; // +++

OrthographicCamera cam; // +++

SpriteBatch batch;

Texture texture;

public void create () {

batch = new SpriteBatch();

texture = new Texture(Gdx.files.internal("data/badlogic.jpg"));

cam = new OrthographicCamera(); //

cam.setToOrtho(false, VIRTUAL_WIDTH, VIRTUAL_HEIGHT); // +++

batch.setProjectionMatrix(cam.combined); // +++

}

public void render () {

Gdx.gl.glClear(GL20.GL_COLOR_BUFFER_BIT);

batch.begin();

batch.draw(texture, 0, 0);

batch.end();

}

public void dispose () {

texture.dispose();

batch.dispose();

}

}

Which looks something like this:

As you can see, scaling the virtual resolution (the “virtual viewport”) to the actual resolution might cause the result to be stretched when the aspect ratio doesn’t match. To solve this, some sort of scaling strategy has to be used. For example by adding “black bars” or growing/shrinking the width/height depending on difference in aspect ratio. LibGDX comes with various strategies you can chose from (more info and some examples). But for now, to keep things simple, let’s just fix the height at 720 and resize the width according to the actual resolution.

public class LibGDXTest extends ApplicationAdapter {

final float VIRTUAL_HEIGHT = 720;

OrthographicCamera cam;

SpriteBatch batch;

Texture texture;

public void create () {

batch = new SpriteBatch();

texture = new Texture(Gdx.files.internal("data/badlogic.jpg"));

cam = new OrthographicCamera();

}

public void resize (int width, int height) { // +++

cam.setToOrtho(false, VIRTUAL_HEIGHT * width / (float)height, VIRTUAL_HEIGHT); // +++

batch.setProjectionMatrix(cam.combined); // +++

} // +++

public void render () {

Gdx.gl.glClear(GL20.GL_COLOR_BUFFER_BIT);

batch.begin();

batch.draw(texture, 0, 0);

batch.end();

}

public void dispose () {

texture.dispose();

batch.dispose();

}

}

So, let’s assume that we’re using this approach to create a game. Our hero in the game, the texture of 256 width by 256 height, is just slightly bigger than one third of the height of the screen, which is always 720 in height. Let’s say, for the sake of the example, that the goal of the game is to make the hero jump to the top of the screen. Every time the user taps the screen, the hero goes up a bit. Meanwhile gravity will make it go down.

public class LibGDXTest extends ApplicationAdapter {

final float VIRTUAL_HEIGHT = 720;

OrthographicCamera cam;

SpriteBatch batch;

Texture texture;

float y; // +++

float gravity = -9.81f; // +++ earths gravity is around 9.81 m/s^2 downwards

float velocity; // +++

float jumpHeight = 1f; // +++ jump 1 meter every time

public void create () {

batch = new SpriteBatch();

texture = new Texture(Gdx.files.internal("data/badlogic.jpg"));

cam = new OrthographicCamera();

}

public void resize (int width, int height) {

cam.setToOrtho(false, VIRTUAL_HEIGHT * width / (float)height, VIRTUAL_HEIGHT);

batch.setProjectionMatrix(cam.combined);

}

public void render () {

if (Gdx.input.justTouched()) // +++

y += jumpHeight; // +++

float delta = Math.min(1/10f, Gdx.graphics.getDeltaTime()); // +++

velocity += gravity * delta; // +++

y += velocity * delta; // +++

if (y <= 0) // +++

y = velocity = 0; // +++

Gdx.gl.glClear(GL20.GL_COLOR_BUFFER_BIT);

batch.begin();

batch.draw(texture, 0, y); // +++

batch.end();

}

public void dispose () {

texture.dispose();

batch.dispose();

}

}

This immediately shows quite an issue with this code: the gravity is expressed in meter per second per second and the jumpHeight is expressed in meter, while the location of the hero is expressed within the virtual resolution. We’ll have to somehow convert between the two.

Let’s say that the typical hero is around 1.8 meters. The hero in our virtual resolution is 256 in height. We can compensate for that by using a constant value:

public class LibGDXTest extends ApplicationAdapter {

final float VIRTUAL_HEIGHT = 720;

final float PIXELS_PER_METER = 256f / 1.8f; // +++

OrthographicCamera cam;

SpriteBatch batch;

Texture texture;

float y;

float gravity = -9.81f; // earth gravity is +/- 9/81 m/s^2 downwards

float velocity;

float jumpHeight = 1f; // jump 1 meter every time

public void create () {

batch = new SpriteBatch();

texture = new Texture(Gdx.files.internal("data/badlogic.jpg"));

cam = new OrthographicCamera();

}

public void resize (int width, int height) {

cam.setToOrtho(false, VIRTUAL_HEIGHT * width / (float)height, VIRTUAL_HEIGHT);

batch.setProjectionMatrix(cam.combined);

}

public void render () {

if (Gdx.input.justTouched())

y += jumpHeight;

float delta = Math.min(1/10f, Gdx.graphics.getDeltaTime());

velocity += gravity * delta;

y += velocity * delta;

if (y <= 0)

y = velocity = 0;

Gdx.gl.glClear(GL20.GL_COLOR_BUFFER_BIT);

batch.begin();

batch.draw(texture, 0, y * PIXELS_PER_METER); // +++

batch.end();

}

public void dispose () {

texture.dispose();

batch.dispose();

}

}

This is approach is sometimes used when using box2d for physics. This blog post suggest you could use this approach, although it also advises not to do so.

So by using a PIXELS_PER_METER constant (sometimes called PPM or alike) we can now use real-world physics in our virtual resolution (e.g. by using the box2d extension).

Let’s assume we’d actually take this approach and publish our game. Our game would look great on 720 height screens, but probably not so much on other screens. This is because the texture would be pixel perfect on 720 (height) screens, but would be up-scaled or down-scaled for other resolutions. We could solve this by using different textures for different screen resolution (e.g. SD vs HD). Luckily libGDX comes with a nice helper class to load assets depending on device resolution: ResolutionFileResolver.

public class Basic3DTest extends ApplicationAdapter {

final float VIRTUAL_HEIGHT = 720;

final float PIXELS_PER_METER = 256f / 1.8f;

ResolutionFileResolver fileResolver; // +++

OrthographicCamera cam;

SpriteBatch batch;

Texture texture;

float y;

float gravity = -9.81f; // earth gravity is +/- 9.81 m/s^2 downwards

float velocity;

float jumpHeight = 1f; // jump 1 meter every time

public void create () {

fileResolver = new ResolutionFileResolver(new InternalFileHandleResolver(), new Resolution(800, 480, "480"), // +++

new Resolution(1280, 720, "720"), new Resolution(1920, 1080, "1080")); // +++

batch = new SpriteBatch();

texture = new Texture(fileResolver.resolve("data/badlogic.jpg")); // +++

cam = new OrthographicCamera();

}

public void resize (int width, int height) {

cam.setToOrtho(false, VIRTUAL_HEIGHT * width / (float)height, VIRTUAL_HEIGHT);

batch.setProjectionMatrix(cam.combined);

}

public void render () {

if (Gdx.input.justTouched()) y += jumpHeight;

float delta = Math.min(1 / 10f, Gdx.graphics.getDeltaTime());

velocity += gravity * delta;

y += velocity * delta;

if (y <= 0) y = velocity = 0;

Gdx.gl.glClear(GL20.GL_COLOR_BUFFER_BIT);

batch.begin();

batch.draw(texture, 0, y * PIXELS_PER_METER);

batch.end();

}

public void dispose () {

texture.dispose();

batch.dispose();

}

}

Of course this would cause the size of our hero to be different depending on the asset size, while we always want it to be 256 x 256. We could easily fix that by specifying the desired size while drawing the texture:

public class Basic3DTest extends ApplicationAdapter {

final float VIRTUAL_HEIGHT = 720;

final float PIXELS_PER_METER = 256f / 1.8f;

ResolutionFileResolver fileResolver;

OrthographicCamera cam;

SpriteBatch batch;

Texture texture;

float y;

float gravity = -9.81f; // earth gravity is +/- 9.81 m/s^2 downwards

float velocity;

float jumpHeight = 1f; // jump 1 meter every time

public void create () {

fileResolver = new ResolutionFileResolver(new InternalFileHandleResolver(), new Resolution(800, 480, "480"),

new Resolution(1280, 720, "720"), new Resolution(1920, 1080, "1080"));

batch = new SpriteBatch();

texture = new Texture(fileResolver.resolve("data/badlogic.jpg"));

cam = new OrthographicCamera();

}

public void resize (int width, int height) {

cam.setToOrtho(false, VIRTUAL_HEIGHT * width / (float)height, VIRTUAL_HEIGHT);

batch.setProjectionMatrix(cam.combined);

}

public void render () {

if (Gdx.input.justTouched()) y += jumpHeight;

float delta = Math.min(1 / 10f, Gdx.graphics.getDeltaTime());

velocity += gravity * delta;

y += velocity * delta;

if (y <= 0) y = velocity = 0;

Gdx.gl.glClear(GL20.GL_COLOR_BUFFER_BIT);

batch.begin();

batch.draw(texture, 0, y * PIXELS_PER_METER, 256f, 256f); // +++

batch.end();

}

public void dispose () {

texture.dispose();

batch.dispose();

}

}

If you think that any of the above makes sense, then please keep reading. We’ve just managed to over-complicate our game at no gain at all. So what’s wrong with this aproach?

It aren’t pixels

Let’s start by terminology. A pixel is an actual thing. A pixel is something you can look at and is stored in memory. There’s no such thing as a “virtual pixel”. For example if you look very very closely at your screen then you can see it is actually made up of pixels (little lights so to speak), each of which can have a different color. Likewise an image is stored on disk or memory as an array of pixels, which is a two dimensional array of colors.

There are two kind of pixels we could have: source and target. The source refers to the source image/texture, these are typically called texels instead of pixels. The target refers often refers to the actual screen, but it could also be a framebuffer (when rendering to texture).

As such, you can’t have fractional pixels, pixels are integers. There’s no such thing as 1.5 pixel. This also implies that if you would specify a location in pixels that it only would be able to move at minimum 1 pixel per frame, regardless framerate.

Potato units

So the units we’ve used in the above example aren’t actually pixels. It are imaginary units which are not related to actual pixels. These are referred to as potato units or banana units, to make sure that you won’t confuse them actual pixels. Nonetheless it could still be useful to use them, doesn’t it?

Sure you can use whatever units you want. If you really want to use potato units (imaginary pixels) then you are free to use them. In fact, when creating a GUI or rendering fonts it might be sometimes useful to work with units that are near pixel-perfect. So for GUI it can be sometimes useful to use potato units. Although your GUI probably should be different depending on screen size and density, e.g. you don’t want to have tiny buttons on phones which are impossible to touch or huge buttons on tablets taking up all the space. So using, for example, the actual screen size in inches or centimeters, might be a better choice (keep in mind that you can use multiple camera’s).

If you do decide to use potato units, then make sure to keep in mind that it aren’t pixels. If you don’t be careful it can very easy to confuse the two, causing all kind of problems. For example, a common mistake is to use touch coordinates (which are actual pixels) without converting them to potato units. Another common mistake is to rely on asset size (like we first did in the above example). Because of these reasons, it is probably better to avoid using “pixels” all together.

There are no pixels

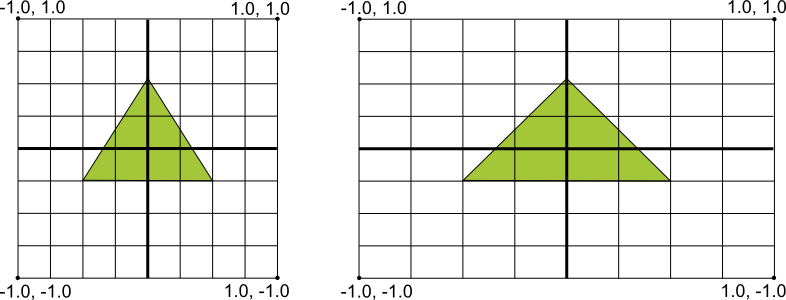

Even if you would make your game the size (in pixels) of the screen, then still it wouldn’t be actual pixels. This is because opengl uses normalized values for both source (the texture) and target (the screen) coordinates. Whatever coordinate system you chose, it will always be normalized. Which means that it will be converted into the range between x:-1,y:-1 for the lower left corner of the screen and x:1,y:1 for the upper right corner of the screen:

This conversion is done using the cam.combined projection matrix we’ve used in the above examples.

What you should do

Let’s forget about pixels, let’s think about meaningful units, e.g. SI units. It’s all about game logic! Which units fit your game best? Always separate game logic from render logic. If your game is best expressed in meters, then use meters. If it is best expressed in inches, then use inches.

So what if we would use meters instead of potato units:

public class Basic3DTest extends GdxTest {

final float VIRTUAL_HEIGHT = 4f; // +++ The virtual height is 4 meters

ResolutionFileResolver fileResolver;

OrthographicCamera cam;

SpriteBatch batch;

Texture texture;

float y;

float gravity = -9.81f; // earth gravity is +/- 9.81 m/s^2 downwards

float velocity;

float jumpHeight = 1f; // jump 1 meter every time

public void create () {

fileResolver = new ResolutionFileResolver(new InternalFileHandleResolver(), new Resolution(800, 480, "480"),

new Resolution(1280, 720, "720"), new Resolution(1920, 1080, "1080"));

batch = new SpriteBatch();

texture = new Texture(fileResolver.resolve("data/badlogic.jpg"));

cam = new OrthographicCamera();

}

public void resize (int width, int height) {

cam.setToOrtho(false, VIRTUAL_HEIGHT * width / (float)height, VIRTUAL_HEIGHT);

batch.setProjectionMatrix(cam.combined);

}

public void render () {

if (Gdx.input.justTouched()) y += jumpHeight;

float delta = Math.min(1 / 10f, Gdx.graphics.getDeltaTime());

velocity += gravity * delta;

y += velocity * delta;

if (y <= 0) y = velocity = 0;

Gdx.gl.glClear(GL20.GL_COLOR_BUFFER_BIT);

batch.begin();

batch.draw(texture, 0, y, 1.8f, 1.8f); // +++

batch.end();

}

public void dispose () {

texture.dispose();

batch.dispose();

}

}

If a Sprite is used instead of a Texture the correct size has to be applied to the sprite. To keep the origin in the center of the sprite it has to be adjusted too.

sprite.setSize(1.8f, 1.8f);

sprite.setOriginCenter();

This webpage is open source and can be found at: https://github.com/xoppa/xoppa.github.io.

The accompanying sources can be found at: https://github.com/xoppa/blog.

Let me know what you think about this post in the comments below. If you need help then please use the forum instead. If you found an issue with this post then please report an issue or send a pull request.